Pacta Sunt Servanda - TreatyNotifier

Blogs about everything treaty, Favourite treaty topics are Private International Law and Intellectual Property. Regional focus on the European Union (and relationship of treaty law with EU law) and the Netherlands

Translate into your preferred language

Tuesday, August 30, 2016

Constitutioneel Hof Sint Maarten

And now for something completely different. Those following this blog and my twitter posts, know that I am particularly interested (besides treaties) in the effect of treaties and legislation on the former Netherlands Antilles and the interaction between those jurisdictions and the Kingdom of the Netherlands. I therefore started a new blog on the Constitutional Court of Sint Maarten, also because i) no such sight exists, and ii) it is the only court capable of constitutional evaluation in the Netherlands. The site is available at constitutioneelhof.wordpress.com and contains the full text of all (3) decisions in all (2) cases up till today. As far as I know it is the only site with the texts of those decisions in a format in which copy-pasting is possible. Feel free to do so (there is no copyright on judicial decisions in the Kingdom) or to link to those decisions directly!

Friday, July 15, 2016

CJEU in Brite Strike disagrees with Advocate-General, but comes to the same conclusion

Yesterday CJEU published its decision in the case Brite Strike (C-230/15), a case regarding the Benelux Trademark "BriteStrike" in which the US mother company BrightStrike brought proceedings about a Luxembourg-based former licensee that had registered the mark.

It brought those proceedings before the Rechtbank Den Haag (Court of The Hague). Based on the so called Brussels I regulation (Regulation 44/2001 at the time; now 1215/2012) that court would have jurisdiction based on article 22.4 of the regulation (which gives -amongst others- jurisdiction to the courts of the country where registration has taken place) as the Benelux trademark is administered by the Benelux Organisation for Industrial Property located in The Hague.

Jurisdiction rules within the 2005 Benelux Convention for Industrial Property (BCIP) however explicitly disallow the place of registration as a connecting factor leading to jurisdiction. In the case of disputes regarding validity of marks, it grants jurisdiction to the location where the seat of the trademark owner is: Luxembourg.

A few years ago the Dutch Hague Court of Appeal decided that not the Benelux Convention, but the Brussels I convention was relevant for determining jurisdiction, after which Dutch courts would evaluate jurisdiction on both conventions, and -in case of a conflicting conclusion- would suggest to ask CJEU.

The discussion in Dutch courts was almost a philosophical one. Since entry into force of the Brussels I regulation new conventions on jurisdiction between member states are not allowed anymore. The 2005 BCIP was clearly newer and thus was not allowed to take precedence (as the Hague court of appeal held), but it took its jurisdiction rules directly from the much older Benelux Convention on Trademarks and the Benelux Convention on Industrial Designs that it replaced. In other words, there were "old" jurisdiction rules about "old" Benelux IP rights, copy pasted in a "new" BCIP convention.

The AG opinion took this as the most important issue to be settled and concluded that the convention should be deemed a continuation of the old conventions, and thus an "old" convention within the meaning of Brussels I. It only added one extra requirement for the Benelux rules to be allowed to take precedence: they must not go against the fundamental principles of EU law. To me a surprise in itself, as that would amount to a non-literal interpretation of the Brussels I regulation, which has been the rule in the past years. The AG took Article 350 (see below) of the TFEU as an additional argument for choosing such an interpretation

The Court took its decision only 2 months after the AG decision and added a point to the discussion that was previously not part of the debate: the fact that Benelux trademarks are.. Benelux trademarks. As the AG already had alluded, The Benelux Union has a special place in Article 350 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union:

1) Rules can only remain in force to the extent the Benelux "is further advanced than the internal market"

This was the case according to CJEU, when it compared the regulations regarding harmonisation of national trademarks with the Benelux trademarks (one could however also say that the Benelux is not more advanced, because with the Union Trademark, the EU is just as advanced!)

2) The rules are indispensable for the proper functioning of the Benelux system

The court found an argument for this in the fact that the EU regulator had also deemed Brussels I unsuitable for the unitary EU Trademark (where jurisdiction is governed by the EU Trademark Regulation), and also by the fact that multiple languages exist in the Benelux thus making a jurisdiction system necessary where the defendant can be heard in his own language.

3) the rules cannot "compromise the principles which underlie judicial cooperation in civil and commercial matters in the European Union"

This last requirement (also suggested by the AG) was held to be fulfilled, especially because the system is place of the defendant-based, which is also a corner stone of the Brussels I regulation.

|

| Brite Strike "tactical lighting" |

Jurisdiction rules within the 2005 Benelux Convention for Industrial Property (BCIP) however explicitly disallow the place of registration as a connecting factor leading to jurisdiction. In the case of disputes regarding validity of marks, it grants jurisdiction to the location where the seat of the trademark owner is: Luxembourg.

A few years ago the Dutch Hague Court of Appeal decided that not the Benelux Convention, but the Brussels I convention was relevant for determining jurisdiction, after which Dutch courts would evaluate jurisdiction on both conventions, and -in case of a conflicting conclusion- would suggest to ask CJEU.

The discussion in Dutch courts was almost a philosophical one. Since entry into force of the Brussels I regulation new conventions on jurisdiction between member states are not allowed anymore. The 2005 BCIP was clearly newer and thus was not allowed to take precedence (as the Hague court of appeal held), but it took its jurisdiction rules directly from the much older Benelux Convention on Trademarks and the Benelux Convention on Industrial Designs that it replaced. In other words, there were "old" jurisdiction rules about "old" Benelux IP rights, copy pasted in a "new" BCIP convention.

Advocate General

|

| Advocate General Henrik Saugmandsgaard Øe |

Court decision

|

| The Benelux, a Union to be allowed "completion" |

The provisions of the Treaties shall not preclude the existence or completion of regional unions between Belgium and Luxembourg, or between Belgium, Luxembourg and the Netherlands, to the extent that the objectives of these regional unions are not attained by application of the Treaties.Based on this article, the court decided it had to establish whether:

1) Rules can only remain in force to the extent the Benelux "is further advanced than the internal market"

This was the case according to CJEU, when it compared the regulations regarding harmonisation of national trademarks with the Benelux trademarks (one could however also say that the Benelux is not more advanced, because with the Union Trademark, the EU is just as advanced!)

2) The rules are indispensable for the proper functioning of the Benelux system

The court found an argument for this in the fact that the EU regulator had also deemed Brussels I unsuitable for the unitary EU Trademark (where jurisdiction is governed by the EU Trademark Regulation), and also by the fact that multiple languages exist in the Benelux thus making a jurisdiction system necessary where the defendant can be heard in his own language.

3) the rules cannot "compromise the principles which underlie judicial cooperation in civil and commercial matters in the European Union"

This last requirement (also suggested by the AG) was held to be fulfilled, especially because the system is place of the defendant-based, which is also a corner stone of the Brussels I regulation.

conclusion

So

-the AG tries to fit the BCIP within te exception of Article 71 of the Brussels I regulation by regarding that treaty as an "older" treaty because it is part of an older system of conventions, using Article 350 TFEU (the "Benelux exception") as an argument

-The Court starts of with Article 350 TFEU (the "Benelux exception") and looks whether article 71 in this case is in conflict with that, and thus should be put aside.

That is quite a different reasoning boiling down to the same conclusion: Benelux rules govern jurisdiction in Benelux Trademarks.

-the AG tries to fit the BCIP within te exception of Article 71 of the Brussels I regulation by regarding that treaty as an "older" treaty because it is part of an older system of conventions, using Article 350 TFEU (the "Benelux exception") as an argument

-The Court starts of with Article 350 TFEU (the "Benelux exception") and looks whether article 71 in this case is in conflict with that, and thus should be put aside.

That is quite a different reasoning boiling down to the same conclusion: Benelux rules govern jurisdiction in Benelux Trademarks.

Especially with regards to point one above, it would be easy for the court to come to the opposite conclusion, which would have required the court to see if it would follow the AG opinions reasoning regarding article 71.

For the Benelux, this decision is more welcome than the AG decision as it reinforces (or at least confirms ) the rights of article 350 TFEU regarding IP rights, even if they are already unified. The Benelux thus could come up with a unitary copyright (or even European patent ;-)) if they wanted to. Whether that is really helpful is a different matter: there seems not much political will to further "complete" the Benelux Union...

Thursday, June 9, 2016

CJEU Case C 230/15: Advocate General advices interpretation "à caractère non formaliste"

On 26 May, European Court of Justice Advocate-General Saugmandsgaard Øe delivered his opinion in case C 230/15 (ECLI:EU:C:2016:366). The case may sound trivial: the The Hague court asked (in ECLI:NL:RBDHA:2015:5716) whether the Dutch courts and/or the Luxembourg courts have jurisdiction regarding the validity of Benelux mark 0877058 "Brite-Strike"?

The case is however relevant to put to rest a difference of judicial opinion on which jurisdiction rules apply regarding Benelux marks (and Benelux industrial designs): those in the Benelux Convention on Intellectual Property (BCIP) or those in the Brussels I regulation (EC 44/2001 when this case started, presently EU 1215/2012). See earlier posts on the exact questions referred to CJEU and how Belgian and Dutch judges have treated the matter in the past years.

Saugmandsgaard Øe is a new CJEU AG, so we have not seen much about him. In this opinion he is -in my opinion- sensible, his opinion can easily be followed, but it seems also slightly activist. Despite the wealth of judgements calling for a literal interpretation of Brussels I, Øe here strongly relies on the intention of the regulation. But I am getting ahead of myself, let's examine his points first:

and that thus -unlike other private international law EU regulations- it does not explicitly replace all pre-existing conventions between EU states. He concludes that 3 requirements have to be met for conventions to have precedence over Brussels I:

The case is however relevant to put to rest a difference of judicial opinion on which jurisdiction rules apply regarding Benelux marks (and Benelux industrial designs): those in the Benelux Convention on Intellectual Property (BCIP) or those in the Brussels I regulation (EC 44/2001 when this case started, presently EU 1215/2012). See earlier posts on the exact questions referred to CJEU and how Belgian and Dutch judges have treated the matter in the past years.

Saugmandsgaard Øe is a new CJEU AG, so we have not seen much about him. In this opinion he is -in my opinion- sensible, his opinion can easily be followed, but it seems also slightly activist. Despite the wealth of judgements calling for a literal interpretation of Brussels I, Øe here strongly relies on the intention of the regulation. But I am getting ahead of myself, let's examine his points first:

This is a general problem

While the case at hand may be solved by giving a narrow answer regarding jurisdiction (focussing on a trademark invalidity rather than infringement of rights etc), the AG agrees with the Dutch court that the general problem is the hierarchy between BCIP and Brussels I and suggests the questions is treated that way (few! any narrowing down would give rise to more questions!).

Two formal requirements; and one more...

The AG first notes that the conflict between other conventions is treated in Article 71.1 and 71.2(a)

1. This Regulation shall not affect any conventions to which the Member States are parties and which in relation to particular matters, govern jurisdiction or the recognition or enforcement of judgments.

2. With a view to its uniform interpretation, paragraph 1 shall be applied in the following manner:

-

(a) this Regulation shall not prevent a court of a Member State, which is a party to a convention on a particular matter, from assuming jurisdiction in accordance with that convention, even where the defendant is domiciled in another Member State which is not a party to that convention. The court hearing the action shall, in any event, apply Article 26 of this Regulation; (...)

- It should govern a particular matter

- the Member States should already be a party to the other convention

- The jurisdiction rules cannot go against the objectives of EU law.

The first point is relatively easy: the jurisdiction rules only govern Benelux Trademarks and Designs (the AG can't stop himself from pointing out that despite the wide scope suggested by the name of the convention on Intellectual Property, it only governs those two types), that that's clearly a particular matter.

Point 2: EU countries should already be a party

This rule was new in the Regulation compared to the Brussels convention it replaced. So from around 2001 (approval of the regulation) or 2003 (entry into force) no new conventions could take precedence anymore. The BCIP is from 2005 and thus clearly a younger (or: posterior) convention and thus the European Commission argued that the convention should not take precedence. Saugsmandsgaard however notices the special character of the 2005 convention: it was a new convention merging and modernising 2 conventions regarding Benelux trademarks (1971) and industrial designs (1975). The jurisdiction rules in those conventions were essentially the same and were merely copied into the 2005 convention. Saugsmandsgaard thus concludes (in an approach he considers "à caractère non formaliste") the jurisdiction rules in relation to the matter they governed (trademarks/designs) should be considered older: the BCIP should thus NOT be regarded a posterior convention.

point 3: The jurisdiction rules cannot go against the objectives of EU law

The third point doesn't stem from an interpretation of the text of article 71 per se, but from CJEU case law. The AG refers to C 533/08 (ECLI:EU:C:2010:243, TNT Express v AXA), requires those rules not to be applied against the objectives of EU law:

While it is apparent from the foregoing considerations that Article 71 of Regulation No 44/2001 provides, in relation to matters governed by specialised conventions, for the application of those conventions, the fact remains that their application cannot compromise the principles which underlie judicial cooperation in civil and commercial matters in the European Union, such as the principles, recalled in recitals 6, 11, 12 and 15 to 17 in the preamble to Regulation No 44/2001, of free movement of judgments in civil and commercial matters, predictability as to the courts having jurisdiction and therefore legal certainty for litigants, sound administration of justice, minimisation of the risk of concurrent proceedings, and mutual trust in the administration of justice in the European Union.

In evaluating whether in BCIP this criterion is met, the AG notes that unitary intellectual property rights (the EU Trademark, the Community Design, the unitary patent, but even the European patent as far as proceedings for the EPO are concerned) are always treated specifically as the general Brussels I rules are not adapted to it. The AG thus argues that using the BCIP obtains a better result than applying 44/2001.

Conclusion

The AG thus concludes that BCIP jurisdiction rules should govern Benelux trademarks and designs and thus dismisses decision ECLI:NL:GHDHA:2013:4466 of the Hague Court of Appeal of 2013 that started the confusion: before that case BCIP was always applied without discussion, but that court came to the opposite conclusion (Brussels I prevails) and was so certain that it explicitly remarked that it deemed CJEU questions not necessary. If followed, that is a welcome and sensible outcome!

Labels:

1215/2012,

44/2001,

BCIP,

Benelux,

Brite Strike,

Brussels I,

C-230/15,

CJEU opinions,

jurisdiction

Location:

CJEU, Luxembourg

Tuesday, April 19, 2016

Unified Patent Court and unitary patent in the Netherlands: an update

Last year, as basic information for a public consultation, the Dutch government showed their

* draft approval act of the Unified Patent Court and

* draft act amending the patents act

[I have commented at the consultation regarding my concerns on the implementation for the part of the Kingdom of the Netherlands where the European Patent Convention applies, but not EU law (and thus not the unitary patent regulation), but that is not the point of this post]

The logic step after consultation (and -minor- amendment of the draft implementation act) is to send both draft acts for comment to the Council of State (Raad van State) for its mandatory advice. The Raad van State took its time and only delivered its advice on the amendment of the patents act in January 2016.

After the advice, the Government may amend the draft act, and send it, with the Advice, and its comments on that advice to Parliament. When approving treaties, it is customary to send the implementation act and the approval act of the treaty together, so they can be treated together.

Approval of the Agreement: status

This time however, things went a bit different. The Government placed the draft legislation on a list with urgent draft acts requiring speedy treatment in parliament; and send out the piece a few weeks after the Advice was received, but ... only the approval act of the Unified Patent Court, and NOT the draft patents act amendment, stating that needed more time. Parliament (in this case the House of Representatives, Tweede Kamer) did not sit around and send out its first round of written questions last week (apart from the "usual" questions like if there will be a Dutch local division/language arrangements; in this case also questions regarding who is competent for "searches based on a search warrant in UPC cases" and the link with breeder's rights.

Regarding the Amendments to the patents act, I have no idea what is the status, as the advice of the Council of State is only published upon presenting the draft act to parliament. So we don't know what the cause for the delay is. The amendments concerned 2 main things: bringing terminology between EU legislation, Unified Patent Court Agreement and the Patents act in line, so there would be no discussion (and thus also no divergence between national/classical European Patents and unitary patents), and making sure that after unitary effect was granted, the national/classical Dutch part of the European patent would remain, but only with regards to the Caribbean parts of the Kingdom where the unitary effect does not apply. [My guess is that it is this second change that is causing the government a headache. This headache may be strengthened because patents is one of only 4 areas where the countries in the Kingdom are voluntarily cooperating, and this implementation may be a source of conflict.]

The delay in this act is bound not to end any time soon. In an extremely unusual move, the government last week requested the Advice of the Council of State again. This time not for a new version of the approval act, but in a "verzoek om voorlichting" (a request for education/information) regarding a new European patent system". This can only mean that the government does not know or is in conflict on how to proceed following the advice. We unfortunately don't know the advice, nor do we know the content of the new request, so we'll have to wait and see what happens! It does seriously call into question whether the Netherlands will be amongst the initial users of the Unified Patent Court system: the Netherlands say they can ratify without the implementation act, but in my modest view that would give rise to too much legal uncertainty; it certainly has never been the plan from the beginning. ...

* draft approval act of the Unified Patent Court and

* draft act amending the patents act

[I have commented at the consultation regarding my concerns on the implementation for the part of the Kingdom of the Netherlands where the European Patent Convention applies, but not EU law (and thus not the unitary patent regulation), but that is not the point of this post]

The logic step after consultation (and -minor- amendment of the draft implementation act) is to send both draft acts for comment to the Council of State (Raad van State) for its mandatory advice. The Raad van State took its time and only delivered its advice on the amendment of the patents act in January 2016.

After the advice, the Government may amend the draft act, and send it, with the Advice, and its comments on that advice to Parliament. When approving treaties, it is customary to send the implementation act and the approval act of the treaty together, so they can be treated together.

Approval of the Agreement: status

This time however, things went a bit different. The Government placed the draft legislation on a list with urgent draft acts requiring speedy treatment in parliament; and send out the piece a few weeks after the Advice was received, but ... only the approval act of the Unified Patent Court, and NOT the draft patents act amendment, stating that needed more time. Parliament (in this case the House of Representatives, Tweede Kamer) did not sit around and send out its first round of written questions last week (apart from the "usual" questions like if there will be a Dutch local division/language arrangements; in this case also questions regarding who is competent for "searches based on a search warrant in UPC cases" and the link with breeder's rights.

Regarding the Amendments to the patents act, I have no idea what is the status, as the advice of the Council of State is only published upon presenting the draft act to parliament. So we don't know what the cause for the delay is. The amendments concerned 2 main things: bringing terminology between EU legislation, Unified Patent Court Agreement and the Patents act in line, so there would be no discussion (and thus also no divergence between national/classical European Patents and unitary patents), and making sure that after unitary effect was granted, the national/classical Dutch part of the European patent would remain, but only with regards to the Caribbean parts of the Kingdom where the unitary effect does not apply. [My guess is that it is this second change that is causing the government a headache. This headache may be strengthened because patents is one of only 4 areas where the countries in the Kingdom are voluntarily cooperating, and this implementation may be a source of conflict.]

The delay in this act is bound not to end any time soon. In an extremely unusual move, the government last week requested the Advice of the Council of State again. This time not for a new version of the approval act, but in a "verzoek om voorlichting" (a request for education/information) regarding a new European patent system". This can only mean that the government does not know or is in conflict on how to proceed following the advice. We unfortunately don't know the advice, nor do we know the content of the new request, so we'll have to wait and see what happens! It does seriously call into question whether the Netherlands will be amongst the initial users of the Unified Patent Court system: the Netherlands say they can ratify without the implementation act, but in my modest view that would give rise to too much legal uncertainty; it certainly has never been the plan from the beginning. ...

Wednesday, February 24, 2016

Diplomatic fights over Kosovo: Netherlands severely criticized as depositary

Is Kosovo a sovereign state? That's a matter of dispute, not only between Serbia (that considers it part of its territory) and Kosovo itself, but also within its neighbors, the EU and other states. According to wikipedia (who tends to be up to date in view of all discussion about the subject) Kosovo is recognized by 108 out of 193 (56%) United Nations member states. In terms of membership of international organizations, that recognition has not paid off: Kosovo is only a member of the World Bank and IMF. A few months ago an attempt to enter UNESCO failed to obtain the required 2/3 of the vote by only 3%.

The Netherlands has recognized the independence of Kosovo and concluded several agreements in the past years: a readmission agreement between Kosovo and the Benelux states, and a host state agreement on a special tribunal for Kosovo (Kosovo Relocated Specialist Judicial Institution) that is to open its doors in 2016 in The Hague.

But in November last year the Netherlands seems to have made both a technical and a diplomatic error regarding Kosovo, that makes for an interesting annual meeting of the Hague Conference of Private International Law. In both cases concern international conventions for which the Netherlands acts as depositary: administrator of the treaty.

And continued indeed: The depositary re-added Palestine today to the treaty parties, but it kept Kosovo out of the list. The reason? Not mentioned... So still: to be continued.

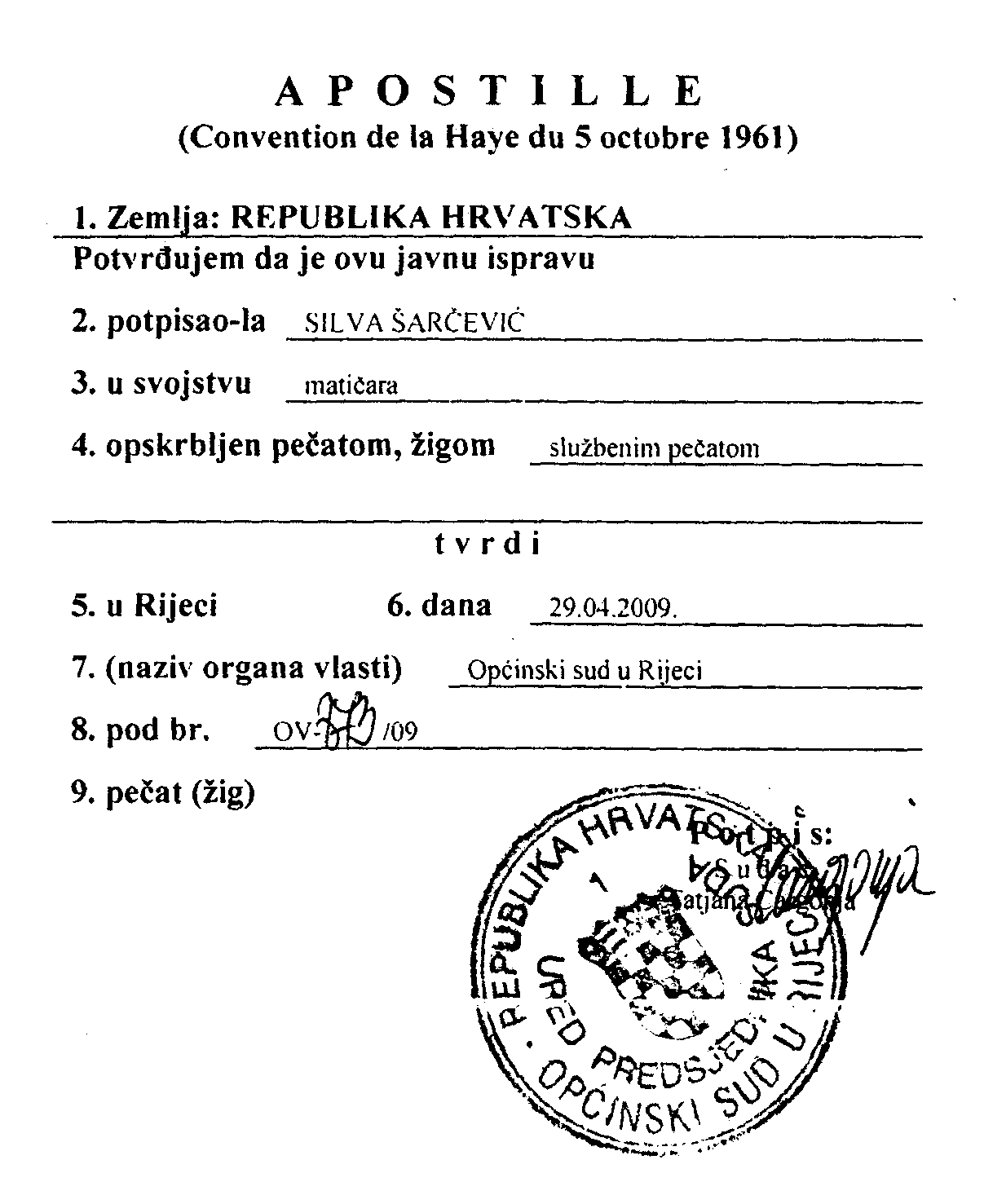

Kosovo acceded to the Apostille convention, formally the Convention abolishing the requirement of legalisation for foreign public documents of 1961 on 6 November 2015, to become its 109th member. The convention allows an easy system to recognize/verify official documents of one convention country in the other, by affixing an Apostille on the document.

Again, objections were lodged, but this time there were two/three categories:

Lots of objections thus, that are in no uncertain term criticizing the depositary, especially for not discussing this with the members of the Hague Conference of Private International law under whose auspicien this convention was drawn up. And indeed, according to article 77.2 of the Vienna Convention (as China points out): that is its duty:

The Netherlands has recognized the independence of Kosovo and concluded several agreements in the past years: a readmission agreement between Kosovo and the Benelux states, and a host state agreement on a special tribunal for Kosovo (Kosovo Relocated Specialist Judicial Institution) that is to open its doors in 2016 in The Hague.

But in November last year the Netherlands seems to have made both a technical and a diplomatic error regarding Kosovo, that makes for an interesting annual meeting of the Hague Conference of Private International Law. In both cases concern international conventions for which the Netherlands acts as depositary: administrator of the treaty.

Error: Convention for the pacific settlement of international disputes

|

| the Peace Palace, seat of the Permanent Court, in The Hague |

The Netherlands is the depositary of the second Hague Peace Conference of 1907 and this convention is a relevant one: it encompasses membership of the Permanent Court of Arbitration and thus a platform for state to state arbitration processes.

The Netherlands received the instruments of accession of Kosovo and Palestine within a week of each other in October/November 2015, and send out standard notifications to the parties, followed by "the standard" objections of the states Georgia, Russia (regarding Kosovo) and Canada and Israel (regarding Palestine). The most to the point reaction however came from the United States, who clearly has done its homework regarding eligibility to accede:

On the basis of this subsequent agreement of the parties to the Convention, eligibility to accede to the Convention has been extended to UN member states. The Government of the United States is not aware of any subsequent decision of the parties to the Convention to extend eligibility to accede to the Convention to entities that are not members of the United Nations.It took the Netherlands only a few days to remove Kosovo and Palestine again from the entry in its treaty database, but it did not send out a notification retracting the depositary notification. To be continued thus...

And continued indeed: The depositary re-added Palestine today to the treaty parties, but it kept Kosovo out of the list. The reason? Not mentioned... So still: to be continued.

Diplomatic error: Apostille Convention

|

| A Croatian Apostille |

Again, objections were lodged, but this time there were two/three categories:

- Objections regarding the accession of what was considered not a state (Russia, Serbia, Georgia, Spain, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Moldova)

- Objections based on Article 12 of the convention; a method through which states may preventing the convention entering into force between them. (China, on behalf of Hong Kong and Macao)

- A combination of both objections (Cyprus, Mexico, Romania)

While Article 12 objections are quite common to new acceding states, the first type of objection is rare. The strong criticism of the actions of the Netherlands is -in diplomatic circles- also rare. A few "juicy" quotes:

- Serbia (in its third(!) note on the matter): Under these circumstances, it should be a duty to the depositary not to receive the instrument of ratification of the Kosovo authorities, or at least to suspend its deposition until the proper decision of the organs of the Hague Conference.

- Spain: Under these circumstances, the Embassy of Spain requests the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Kingdom of the Netherlands not to receive the instrument of accession of this territory to the Apostille Convention or, at least, to suspend its deposition until a proper decision could be adopted by the competent organs of the Hague Conference on Private Law.

- Cyprus: (....) without prior consultation with the state-parties, sets a precarious precedent.

- Georgia does not recognize that the depositary has the power to undertake actions under the Apostille Convention, the treaty practice or public international law that may be construed as direct or implied qualification of entities as states. Georgia pursuing its state interests, considers unacceptable and dangerous adoption of such a practice.

- China: The Embassy noted that relevant States have raised objections to the acceptance of Kosovo's accession by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Netherlands as the Depositary, and reminds the Dutch side to take appropriate actions in accordance with Article 77.2 of the Vienna Convention on the Law of the Treaties.

Lots of objections thus, that are in no uncertain term criticizing the depositary, especially for not discussing this with the members of the Hague Conference of Private International law under whose auspicien this convention was drawn up. And indeed, according to article 77.2 of the Vienna Convention (as China points out): that is its duty:

77.2. In the event of any difference appearing between a State and the depositary as to the performance of the latter's functions, the depositary shall bring the question to the attention of the signatory States and the contracting States or, where appropriate, of the competent organ of the international organization concerned.The last point is indeed what seems to be the way forward. The Hague Conference happens to have its annual meeting (its Council on General Affairs and Policy) in 15-17 March in The Hague and its agenda now has the item:

- 3. New ratifications / accessions: the roles of the Depository & the Permanent Bureau (subject to further developments)

It's to be hoped (for the Netherlands and the image of HCCH) that a diplomatic solution will be found before the start of the conference, although I have no idea along which lines that will be. For membership of the Conference (which is not at issue here) unanimity is required, and during conference, consensus shall be the goal. However voting at the conference is based on one-country-one-vote and a simple majority suffices. It seems at this moment impossible to guess what the outcome will be...

UPDATE:Based on the voting during the admission procedure of Kosovo to UNESCO of November, (assuming there is a vote; assuming all states vote; and vote the same; and assuming the EU will not vote, but its member states will), 39 will vote in favour, 25 against and 11 will abstain. The votes 4 five member states are unclear, as they didn't vote during the Kovoso admission.

UPDATE:Based on the voting during the admission procedure of Kosovo to UNESCO of November, (assuming there is a vote; assuming all states vote; and vote the same; and assuming the EU will not vote, but its member states will), 39 will vote in favour, 25 against and 11 will abstain. The votes 4 five member states are unclear, as they didn't vote during the Kovoso admission.

Friday, January 22, 2016

Unified Patent Court and Unitary Patent: what UK and NL can learn from eachother

Two days ago, I have placed myself in the perspective of the Isle of Man, and 5 islands of the former Netherlands Antilles in order to discuss the different modes of implementation for the unitary patent and the unified patent court the Netherlands and the UK have chosen with regards to their "dependent territories". Todays post is an advice to both governments. Their legislative proposals both have merit to some extent and they could lear from each other. Combined with a good "Treaty-notifier" advice, in my opinion the system should be implemented like this:

Unified Patent Court: Netherlands should listen to the UK

The Unified Patent Court Agreement (UPCA) is silent on whether it can be extended to dependent territories. While regarding European patents without unitary effect its decisions have effect on the territories, it is not clear whether infringement actions on the territories would be covered. The preambule starting with characterisation of the signatories as "Member States of the European Union" could suggest that the territorial scope is that of the EU, and thus does not cover the territories.

The UK bluntly states that it will extend the treaty to the Isle of Man, and thus the UPC will full apply. It seems a judgement call whether this is possible, in which the depositary (Council of the EU) has a final say, but if they do (and I think they will, in treaties, a lot of latitude is given with regard to extensions generally when the treaty is silent on it), then it is by far the easiest way to keep the European patent "uniform" within UK+Isle and NL+Curacao+CaribbeanNetherlands+SintMaarten.

Unitary Patent: UK should listen to the Netherlands

The Unitary patent is governed by the Unitary Patent Regulation, an EU Regulation, which territorial scope is the territorial scope of the EU and excludes these territories. The UK may state that by ratifying the UPCA, the territorial extent of the Unitary Patent Regulation will extend to the territories, but that's would be the first time the territorial scope of a Regulation is extended in this way [the EU, NL, and UK could enter into a treaty of course that extends certain regulations to the territories, but that's a long term solution]. The Dutch made a more clear interpretation of the interaction of the Unitary Patent Regulation with the European Patent Convention: if the "national" European patent without unitary effect will be assumed never to have taken effect when the unitary effect is granted, that has no effect for the territories not covered by the unitary effect. In other words, the unitary effect does not have the effect that the national European patent disappears, but its territorial scope is reduced to the Isle of Man and remains in existence as national European patent under national law. In the UK this is the EP-unitary and the EP-UK coexist, where the latter is best identified as EP-UK-"EPCnonEU" ("European patent in effect as a national UK patent with a territorial scope of the territory under the EPC, but not the territory of the EU: EP valid in the Isle of Man only), to identify its -very- limited territorial scope as a residual national European patent.

Law applicable to EP-UK-"EPCnonEU" and EP-NL-"EPCnonEU": a suggestion from me

National law still applies to the EP-UK-"EPCnonEU" (EP Isle of Man) and the corresponding residual Dutch national residual European patent (EP-NL_"EPCnonEU"). That means separate renewal fees etc and thus extra costs and handling. Luckily, if implemented as described, the UPC has jurisdiction. However -unlike the corresponding unitary patent- during the transition period the residual European patent may also be tried in national courts.

In order not to make the treatment of residual European patents different from the unitary patent, I propose to include regulations in the national laws, in which the residual European patents as much as possible have the same effect as the unitary patent. That means they apply the unitary patent regulation as a matter of national law. The implementation should make sure that the residual European patents are really "glued to the unitary patent" by the following provisions regarding residual European patents:

-Exclusive competence for the Unified Patent Court (also during the transition phase)

-any change in the text of the unitary patent will have automatically the same effect for the residual European patents

-the law applicable to residual European patents is that of unitary patents (as an object of property)

-residual European Patents can not be separately owned, morgaged etc. The ownership etc follows automatically that of the unitary patent

-a license of a unitary patent including the territory of the main office of UKIPO, automatically also is covering the Isle of Man

-a license of a unitary patent including the territory of the main office of the Dutch national patent office, automatically also is covering the Curacao, Sint Maarten and the Caribbean Netherlands.

Implementation?

Let's see if this is implemented. We haven't seen the statutory instrument for implementation of the Isle, so it is still possible this was planned all along (although that is not what is suggested in earlier documents). Furthtermore, the final proposed legislation in the Netherlands is unknown and still unpublished. It furthermore can be amended by parliament.

In other words, there is still time to implement this and have the territories covered in a decent and consistent way.

Wednesday, January 20, 2016

Unified Patent Court and Unitary Patent in Isle of Man and other territories

Imagine, just try to imagine, you are a territory. Not just any territory... No, you have a close relationship with the European Union state responsible for your external affairs, but you are -regarding most issues- not part of the EU. Your EU member state is also a European Patent Convention contracting state and has extended application also to you: a European patent in force in "your" EU state, also applies in you. In fact, when the EPC thinks about the member state responsible for your external affairs, it deems that your territory is covered by it.

The answer is complicated, that's clear from the discussion above and it is a pity that the drafters of the unitary patent regulation and UPC agreement have not been more clear in their drafting. That means the answer is i) unclear and ii) varies by territory

If you are an EPC-covered territory connected to the Netherlands (Caribbean Netherlands, Curaçao or Sint Maarten), your government considers, even after suggestions not to in a public consultation (see my blogposts here, here and here):

However, we still don't really know, as the act has not been presented in its final form to parliament.

If you are an EPC-covered territory connected to France, then we still have no idea. The approval law is silent and no provisions were made. I guess, you'll just have to wait and see.

If you are an EPC-covered territory connected to the UK, then you must be... the Isle of Man. That means you have requested in 2013 already to be part of the unified patent court. And today, the UK government has given you most of the required clarity today

My suggestions: after joining, ask your member states to

Who knows, they well might listen!

Change!

But, things are about to change for you, little territory! Several EPC contracting states have made an agreement giving "unitary effect" to European patents in their territory, thus ao solving the problem that different decisions may be made by judiciaries regarding the same patent. From an EPC point of view, you are fully included in that agreement and the unitary effect will also apply to you. Unfortunately however these EPC contracting states have shaped their agreement regarding unitary effect as European Union Regulation 1257/2012, in which they state in Article 1(2) it is also an Agreement in the context of EPC Article 142. Now, article 142 EPC agreements of your contracting state apply to you, but European Union regulations generally don't apply.

Your contracting state has also signed the Unified Patent Court Agreement. It's clear that applies to you regarding litigation on non-unitary-effect European patents as is explicit from Article 34:

"Decisions of the Court shall cover, in the case of a European patent [without unitary effect], the territory of those Contracting Member States for which the European patent has effect."But for European patents with unitary effect that's not so clear because their jurisdiction is arranged in EU instruments. Whether the agreement as a whole applies to you is also unclear, as the agreement is silent with regards to it, but... it is concluded between the contracting parties "member states of the European Union", and you are not considered part of the territorial scope of EU instruments.

So what applies to you?

So, the big question remains: does the unified patent court agreement as a whole apply to you and does the unitary patent apply to you. And if not? what then? What happens if your EU member state's European patent gets unitary effect, and you are left as ..., well as what?The answer is complicated, that's clear from the discussion above and it is a pity that the drafters of the unitary patent regulation and UPC agreement have not been more clear in their drafting. That means the answer is i) unclear and ii) varies by territory

If you are an EPC-covered territory connected to the Netherlands (Caribbean Netherlands, Curaçao or Sint Maarten), your government considers, even after suggestions not to in a public consultation (see my blogposts here, here and here):

- i) the unified patent agreement can not apply to you (and even uses an approval procedure for the agreement excluding you! despite Article 34 above)

- ii) unitary patents don't apply to you. If a European patent gets unitary effect, a small mini non-European patent will remain (called by me EP-NL-carib), covering just you and your fellow territories. What it costs is unknown, but you'll have to pay renewal fees and fulfil translation requirements.

However, we still don't really know, as the act has not been presented in its final form to parliament.

If you are an EPC-covered territory connected to France, then we still have no idea. The approval law is silent and no provisions were made. I guess, you'll just have to wait and see.

If you are an EPC-covered territory connected to the UK, then you must be... the Isle of Man. That means you have requested in 2013 already to be part of the unified patent court. And today, the UK government has given you most of the required clarity today

- i) it will extend the Unified Patent Court Agreement to you (jay!)

- ii) that means -according to the UK- that the unitary patent regulation will also apply to you. Unfortunately it is unclear why your government thinks this is possible. That's problematic: it is not the UK that determines the territorial scope of the Regulation but -at least in last instance- the CJEU that decides that. So I am not sure if you are fully satisfied by this solution. Of course the UK could unilaterally consider it applies unitary patent legislation to you (which could also be implemented as my favourite implementation strategy: after the unitary patent applies in the UK, a national European patent -EU(UK-Man) remains, just covering you, to which -as stated in national law- the unitary patent rules apply; which means in practise: you're covered by the unitary patent). But if that's the case and infringement takes place in your territory, will the Unified Patent Court take jurisdiction?

Conclusion:

The present situation for you as a territory is either uncertain (French territories), certain and as requested but with legal risks (UK-related) or undesirable and legally incorrect (Dutch territories). Maybe it's time to call your fellow territories and together demand the clarity and a clear route how to implement that!My suggestions: after joining, ask your member states to

- change the UPC to explicitly allow extending the UPC agreement to non-EU territories, part of the EPC (and that is a change that doesn't require a diplomatic conference or ratification by all)

- ask your member state to conclude an international agreement between NL, UK, FR and the EU, extending the scope of the Unitary patent regulation to you, in a similar way that many EU regulations are applied to Norway, Iceland and Liechtenstein (the famous "texts with EEA relevance").

Who knows, they well might listen!

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)