Last year, as basic information for a public consultation, the Dutch government showed their

* draft approval act of the Unified Patent Court and

* draft act amending the patents act

[I have commented at the consultation regarding my concerns on the implementation for the part of the Kingdom of the Netherlands where the European Patent Convention applies, but not EU law (and thus not the unitary patent regulation), but that is not the point of this post]

The logic step after consultation (and -minor- amendment of the draft implementation act) is to send both draft acts for comment to the Council of State (Raad van State) for its mandatory advice. The Raad van State took its time and only delivered its advice on the amendment of the patents act in January 2016.

After the advice, the Government may amend the draft act, and send it, with the Advice, and its comments on that advice to Parliament. When approving treaties, it is customary to send the implementation act and the approval act of the treaty together, so they can be treated together.

Approval of the Agreement: status

This time however, things went a bit different. The Government placed the draft legislation on a list with urgent draft acts requiring speedy treatment in parliament; and send out the piece a few weeks after the Advice was received, but ... only the approval act of the Unified Patent Court, and NOT the draft patents act amendment, stating that needed more time. Parliament (in this case the House of Representatives, Tweede Kamer) did not sit around and send out its first round of written questions last week (apart from the "usual" questions like if there will be a Dutch local division/language arrangements; in this case also questions regarding who is competent for "searches based on a search warrant in UPC cases" and the link with breeder's rights.

Regarding the Amendments to the patents act, I have no idea what is the status, as the advice of the Council of State is only published upon presenting the draft act to parliament. So we don't know what the cause for the delay is. The amendments concerned 2 main things: bringing terminology between EU legislation, Unified Patent Court Agreement and the Patents act in line, so there would be no discussion (and thus also no divergence between national/classical European Patents and unitary patents), and making sure that after unitary effect was granted, the national/classical Dutch part of the European patent would remain, but only with regards to the Caribbean parts of the Kingdom where the unitary effect does not apply. [My guess is that it is this second change that is causing the government a headache. This headache may be strengthened because patents is one of only 4 areas where the countries in the Kingdom are voluntarily cooperating, and this implementation may be a source of conflict.]

The delay in this act is bound not to end any time soon. In an extremely unusual move, the government last week requested the Advice of the Council of State again. This time not for a new version of the approval act, but in a "verzoek om voorlichting" (a request for education/information) regarding a new European patent system". This can only mean that the government does not know or is in conflict on how to proceed following the advice. We unfortunately don't know the advice, nor do we know the content of the new request, so we'll have to wait and see what happens! It does seriously call into question whether the Netherlands will be amongst the initial users of the Unified Patent Court system: the Netherlands say they can ratify without the implementation act, but in my modest view that would give rise to too much legal uncertainty; it certainly has never been the plan from the beginning. ...

Blogs about everything treaty, Favourite treaty topics are Private International Law and Intellectual Property. Regional focus on the European Union (and relationship of treaty law with EU law) and the Netherlands

Translate into your preferred language

Tuesday, April 19, 2016

Wednesday, February 24, 2016

Diplomatic fights over Kosovo: Netherlands severely criticized as depositary

Is Kosovo a sovereign state? That's a matter of dispute, not only between Serbia (that considers it part of its territory) and Kosovo itself, but also within its neighbors, the EU and other states. According to wikipedia (who tends to be up to date in view of all discussion about the subject) Kosovo is recognized by 108 out of 193 (56%) United Nations member states. In terms of membership of international organizations, that recognition has not paid off: Kosovo is only a member of the World Bank and IMF. A few months ago an attempt to enter UNESCO failed to obtain the required 2/3 of the vote by only 3%.

The Netherlands has recognized the independence of Kosovo and concluded several agreements in the past years: a readmission agreement between Kosovo and the Benelux states, and a host state agreement on a special tribunal for Kosovo (Kosovo Relocated Specialist Judicial Institution) that is to open its doors in 2016 in The Hague.

But in November last year the Netherlands seems to have made both a technical and a diplomatic error regarding Kosovo, that makes for an interesting annual meeting of the Hague Conference of Private International Law. In both cases concern international conventions for which the Netherlands acts as depositary: administrator of the treaty.

And continued indeed: The depositary re-added Palestine today to the treaty parties, but it kept Kosovo out of the list. The reason? Not mentioned... So still: to be continued.

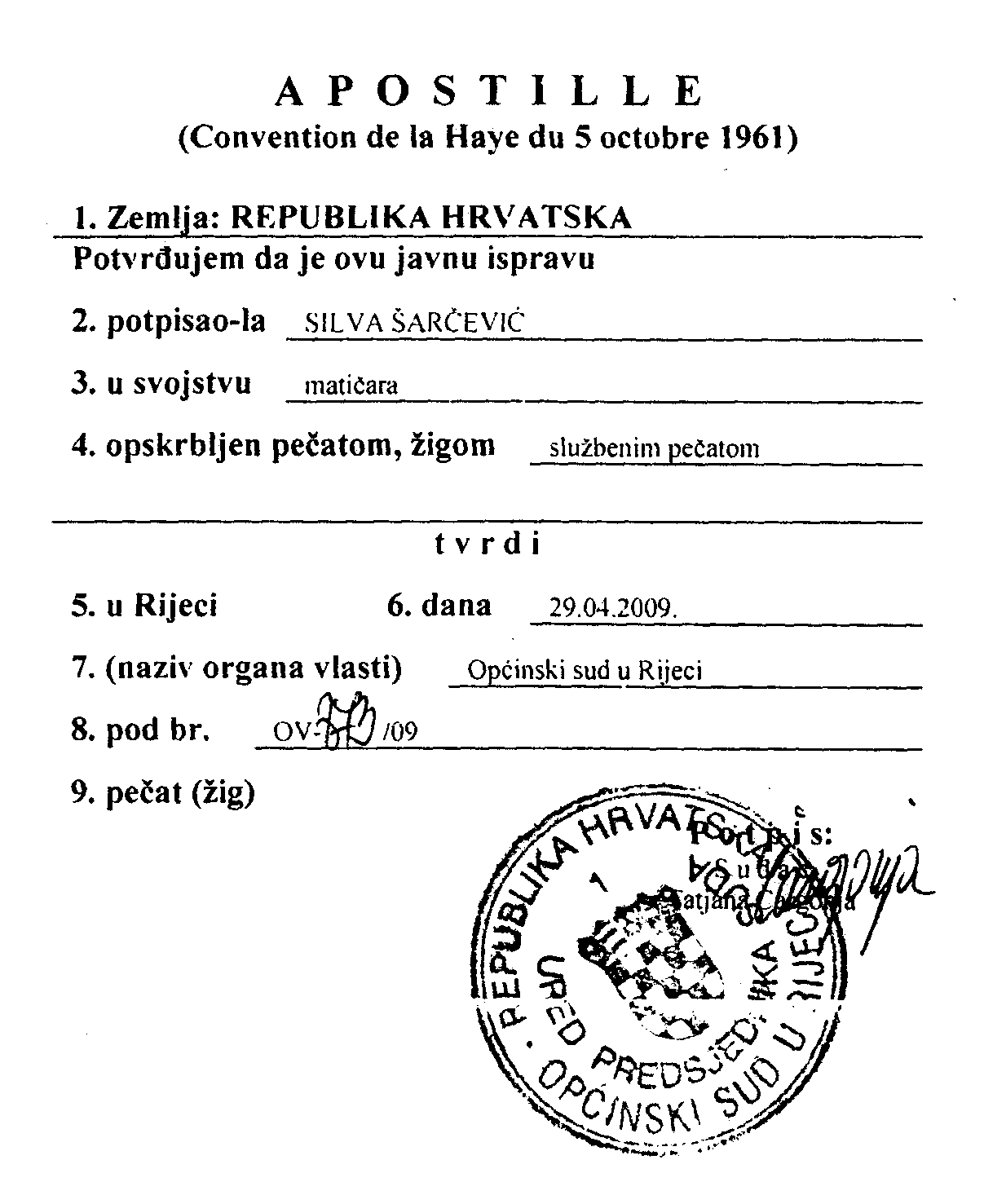

Kosovo acceded to the Apostille convention, formally the Convention abolishing the requirement of legalisation for foreign public documents of 1961 on 6 November 2015, to become its 109th member. The convention allows an easy system to recognize/verify official documents of one convention country in the other, by affixing an Apostille on the document.

Again, objections were lodged, but this time there were two/three categories:

Lots of objections thus, that are in no uncertain term criticizing the depositary, especially for not discussing this with the members of the Hague Conference of Private International law under whose auspicien this convention was drawn up. And indeed, according to article 77.2 of the Vienna Convention (as China points out): that is its duty:

The Netherlands has recognized the independence of Kosovo and concluded several agreements in the past years: a readmission agreement between Kosovo and the Benelux states, and a host state agreement on a special tribunal for Kosovo (Kosovo Relocated Specialist Judicial Institution) that is to open its doors in 2016 in The Hague.

But in November last year the Netherlands seems to have made both a technical and a diplomatic error regarding Kosovo, that makes for an interesting annual meeting of the Hague Conference of Private International Law. In both cases concern international conventions for which the Netherlands acts as depositary: administrator of the treaty.

Error: Convention for the pacific settlement of international disputes

|

| the Peace Palace, seat of the Permanent Court, in The Hague |

The Netherlands is the depositary of the second Hague Peace Conference of 1907 and this convention is a relevant one: it encompasses membership of the Permanent Court of Arbitration and thus a platform for state to state arbitration processes.

The Netherlands received the instruments of accession of Kosovo and Palestine within a week of each other in October/November 2015, and send out standard notifications to the parties, followed by "the standard" objections of the states Georgia, Russia (regarding Kosovo) and Canada and Israel (regarding Palestine). The most to the point reaction however came from the United States, who clearly has done its homework regarding eligibility to accede:

On the basis of this subsequent agreement of the parties to the Convention, eligibility to accede to the Convention has been extended to UN member states. The Government of the United States is not aware of any subsequent decision of the parties to the Convention to extend eligibility to accede to the Convention to entities that are not members of the United Nations.It took the Netherlands only a few days to remove Kosovo and Palestine again from the entry in its treaty database, but it did not send out a notification retracting the depositary notification. To be continued thus...

And continued indeed: The depositary re-added Palestine today to the treaty parties, but it kept Kosovo out of the list. The reason? Not mentioned... So still: to be continued.

Diplomatic error: Apostille Convention

|

| A Croatian Apostille |

Again, objections were lodged, but this time there were two/three categories:

- Objections regarding the accession of what was considered not a state (Russia, Serbia, Georgia, Spain, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Moldova)

- Objections based on Article 12 of the convention; a method through which states may preventing the convention entering into force between them. (China, on behalf of Hong Kong and Macao)

- A combination of both objections (Cyprus, Mexico, Romania)

While Article 12 objections are quite common to new acceding states, the first type of objection is rare. The strong criticism of the actions of the Netherlands is -in diplomatic circles- also rare. A few "juicy" quotes:

- Serbia (in its third(!) note on the matter): Under these circumstances, it should be a duty to the depositary not to receive the instrument of ratification of the Kosovo authorities, or at least to suspend its deposition until the proper decision of the organs of the Hague Conference.

- Spain: Under these circumstances, the Embassy of Spain requests the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Kingdom of the Netherlands not to receive the instrument of accession of this territory to the Apostille Convention or, at least, to suspend its deposition until a proper decision could be adopted by the competent organs of the Hague Conference on Private Law.

- Cyprus: (....) without prior consultation with the state-parties, sets a precarious precedent.

- Georgia does not recognize that the depositary has the power to undertake actions under the Apostille Convention, the treaty practice or public international law that may be construed as direct or implied qualification of entities as states. Georgia pursuing its state interests, considers unacceptable and dangerous adoption of such a practice.

- China: The Embassy noted that relevant States have raised objections to the acceptance of Kosovo's accession by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Netherlands as the Depositary, and reminds the Dutch side to take appropriate actions in accordance with Article 77.2 of the Vienna Convention on the Law of the Treaties.

Lots of objections thus, that are in no uncertain term criticizing the depositary, especially for not discussing this with the members of the Hague Conference of Private International law under whose auspicien this convention was drawn up. And indeed, according to article 77.2 of the Vienna Convention (as China points out): that is its duty:

77.2. In the event of any difference appearing between a State and the depositary as to the performance of the latter's functions, the depositary shall bring the question to the attention of the signatory States and the contracting States or, where appropriate, of the competent organ of the international organization concerned.The last point is indeed what seems to be the way forward. The Hague Conference happens to have its annual meeting (its Council on General Affairs and Policy) in 15-17 March in The Hague and its agenda now has the item:

- 3. New ratifications / accessions: the roles of the Depository & the Permanent Bureau (subject to further developments)

It's to be hoped (for the Netherlands and the image of HCCH) that a diplomatic solution will be found before the start of the conference, although I have no idea along which lines that will be. For membership of the Conference (which is not at issue here) unanimity is required, and during conference, consensus shall be the goal. However voting at the conference is based on one-country-one-vote and a simple majority suffices. It seems at this moment impossible to guess what the outcome will be...

UPDATE:Based on the voting during the admission procedure of Kosovo to UNESCO of November, (assuming there is a vote; assuming all states vote; and vote the same; and assuming the EU will not vote, but its member states will), 39 will vote in favour, 25 against and 11 will abstain. The votes 4 five member states are unclear, as they didn't vote during the Kovoso admission.

UPDATE:Based on the voting during the admission procedure of Kosovo to UNESCO of November, (assuming there is a vote; assuming all states vote; and vote the same; and assuming the EU will not vote, but its member states will), 39 will vote in favour, 25 against and 11 will abstain. The votes 4 five member states are unclear, as they didn't vote during the Kovoso admission.

Friday, January 22, 2016

Unified Patent Court and Unitary Patent: what UK and NL can learn from eachother

Two days ago, I have placed myself in the perspective of the Isle of Man, and 5 islands of the former Netherlands Antilles in order to discuss the different modes of implementation for the unitary patent and the unified patent court the Netherlands and the UK have chosen with regards to their "dependent territories". Todays post is an advice to both governments. Their legislative proposals both have merit to some extent and they could lear from each other. Combined with a good "Treaty-notifier" advice, in my opinion the system should be implemented like this:

Unified Patent Court: Netherlands should listen to the UK

The Unified Patent Court Agreement (UPCA) is silent on whether it can be extended to dependent territories. While regarding European patents without unitary effect its decisions have effect on the territories, it is not clear whether infringement actions on the territories would be covered. The preambule starting with characterisation of the signatories as "Member States of the European Union" could suggest that the territorial scope is that of the EU, and thus does not cover the territories.

The UK bluntly states that it will extend the treaty to the Isle of Man, and thus the UPC will full apply. It seems a judgement call whether this is possible, in which the depositary (Council of the EU) has a final say, but if they do (and I think they will, in treaties, a lot of latitude is given with regard to extensions generally when the treaty is silent on it), then it is by far the easiest way to keep the European patent "uniform" within UK+Isle and NL+Curacao+CaribbeanNetherlands+SintMaarten.

Unitary Patent: UK should listen to the Netherlands

The Unitary patent is governed by the Unitary Patent Regulation, an EU Regulation, which territorial scope is the territorial scope of the EU and excludes these territories. The UK may state that by ratifying the UPCA, the territorial extent of the Unitary Patent Regulation will extend to the territories, but that's would be the first time the territorial scope of a Regulation is extended in this way [the EU, NL, and UK could enter into a treaty of course that extends certain regulations to the territories, but that's a long term solution]. The Dutch made a more clear interpretation of the interaction of the Unitary Patent Regulation with the European Patent Convention: if the "national" European patent without unitary effect will be assumed never to have taken effect when the unitary effect is granted, that has no effect for the territories not covered by the unitary effect. In other words, the unitary effect does not have the effect that the national European patent disappears, but its territorial scope is reduced to the Isle of Man and remains in existence as national European patent under national law. In the UK this is the EP-unitary and the EP-UK coexist, where the latter is best identified as EP-UK-"EPCnonEU" ("European patent in effect as a national UK patent with a territorial scope of the territory under the EPC, but not the territory of the EU: EP valid in the Isle of Man only), to identify its -very- limited territorial scope as a residual national European patent.

Law applicable to EP-UK-"EPCnonEU" and EP-NL-"EPCnonEU": a suggestion from me

National law still applies to the EP-UK-"EPCnonEU" (EP Isle of Man) and the corresponding residual Dutch national residual European patent (EP-NL_"EPCnonEU"). That means separate renewal fees etc and thus extra costs and handling. Luckily, if implemented as described, the UPC has jurisdiction. However -unlike the corresponding unitary patent- during the transition period the residual European patent may also be tried in national courts.

In order not to make the treatment of residual European patents different from the unitary patent, I propose to include regulations in the national laws, in which the residual European patents as much as possible have the same effect as the unitary patent. That means they apply the unitary patent regulation as a matter of national law. The implementation should make sure that the residual European patents are really "glued to the unitary patent" by the following provisions regarding residual European patents:

-Exclusive competence for the Unified Patent Court (also during the transition phase)

-any change in the text of the unitary patent will have automatically the same effect for the residual European patents

-the law applicable to residual European patents is that of unitary patents (as an object of property)

-residual European Patents can not be separately owned, morgaged etc. The ownership etc follows automatically that of the unitary patent

-a license of a unitary patent including the territory of the main office of UKIPO, automatically also is covering the Isle of Man

-a license of a unitary patent including the territory of the main office of the Dutch national patent office, automatically also is covering the Curacao, Sint Maarten and the Caribbean Netherlands.

Implementation?

Let's see if this is implemented. We haven't seen the statutory instrument for implementation of the Isle, so it is still possible this was planned all along (although that is not what is suggested in earlier documents). Furthtermore, the final proposed legislation in the Netherlands is unknown and still unpublished. It furthermore can be amended by parliament.

In other words, there is still time to implement this and have the territories covered in a decent and consistent way.

Wednesday, January 20, 2016

Unified Patent Court and Unitary Patent in Isle of Man and other territories

Imagine, just try to imagine, you are a territory. Not just any territory... No, you have a close relationship with the European Union state responsible for your external affairs, but you are -regarding most issues- not part of the EU. Your EU member state is also a European Patent Convention contracting state and has extended application also to you: a European patent in force in "your" EU state, also applies in you. In fact, when the EPC thinks about the member state responsible for your external affairs, it deems that your territory is covered by it.

The answer is complicated, that's clear from the discussion above and it is a pity that the drafters of the unitary patent regulation and UPC agreement have not been more clear in their drafting. That means the answer is i) unclear and ii) varies by territory

If you are an EPC-covered territory connected to the Netherlands (Caribbean Netherlands, Curaçao or Sint Maarten), your government considers, even after suggestions not to in a public consultation (see my blogposts here, here and here):

However, we still don't really know, as the act has not been presented in its final form to parliament.

If you are an EPC-covered territory connected to France, then we still have no idea. The approval law is silent and no provisions were made. I guess, you'll just have to wait and see.

If you are an EPC-covered territory connected to the UK, then you must be... the Isle of Man. That means you have requested in 2013 already to be part of the unified patent court. And today, the UK government has given you most of the required clarity today

My suggestions: after joining, ask your member states to

Who knows, they well might listen!

Change!

But, things are about to change for you, little territory! Several EPC contracting states have made an agreement giving "unitary effect" to European patents in their territory, thus ao solving the problem that different decisions may be made by judiciaries regarding the same patent. From an EPC point of view, you are fully included in that agreement and the unitary effect will also apply to you. Unfortunately however these EPC contracting states have shaped their agreement regarding unitary effect as European Union Regulation 1257/2012, in which they state in Article 1(2) it is also an Agreement in the context of EPC Article 142. Now, article 142 EPC agreements of your contracting state apply to you, but European Union regulations generally don't apply.

Your contracting state has also signed the Unified Patent Court Agreement. It's clear that applies to you regarding litigation on non-unitary-effect European patents as is explicit from Article 34:

"Decisions of the Court shall cover, in the case of a European patent [without unitary effect], the territory of those Contracting Member States for which the European patent has effect."But for European patents with unitary effect that's not so clear because their jurisdiction is arranged in EU instruments. Whether the agreement as a whole applies to you is also unclear, as the agreement is silent with regards to it, but... it is concluded between the contracting parties "member states of the European Union", and you are not considered part of the territorial scope of EU instruments.

So what applies to you?

So, the big question remains: does the unified patent court agreement as a whole apply to you and does the unitary patent apply to you. And if not? what then? What happens if your EU member state's European patent gets unitary effect, and you are left as ..., well as what?The answer is complicated, that's clear from the discussion above and it is a pity that the drafters of the unitary patent regulation and UPC agreement have not been more clear in their drafting. That means the answer is i) unclear and ii) varies by territory

If you are an EPC-covered territory connected to the Netherlands (Caribbean Netherlands, Curaçao or Sint Maarten), your government considers, even after suggestions not to in a public consultation (see my blogposts here, here and here):

- i) the unified patent agreement can not apply to you (and even uses an approval procedure for the agreement excluding you! despite Article 34 above)

- ii) unitary patents don't apply to you. If a European patent gets unitary effect, a small mini non-European patent will remain (called by me EP-NL-carib), covering just you and your fellow territories. What it costs is unknown, but you'll have to pay renewal fees and fulfil translation requirements.

However, we still don't really know, as the act has not been presented in its final form to parliament.

If you are an EPC-covered territory connected to France, then we still have no idea. The approval law is silent and no provisions were made. I guess, you'll just have to wait and see.

If you are an EPC-covered territory connected to the UK, then you must be... the Isle of Man. That means you have requested in 2013 already to be part of the unified patent court. And today, the UK government has given you most of the required clarity today

- i) it will extend the Unified Patent Court Agreement to you (jay!)

- ii) that means -according to the UK- that the unitary patent regulation will also apply to you. Unfortunately it is unclear why your government thinks this is possible. That's problematic: it is not the UK that determines the territorial scope of the Regulation but -at least in last instance- the CJEU that decides that. So I am not sure if you are fully satisfied by this solution. Of course the UK could unilaterally consider it applies unitary patent legislation to you (which could also be implemented as my favourite implementation strategy: after the unitary patent applies in the UK, a national European patent -EU(UK-Man) remains, just covering you, to which -as stated in national law- the unitary patent rules apply; which means in practise: you're covered by the unitary patent). But if that's the case and infringement takes place in your territory, will the Unified Patent Court take jurisdiction?

Conclusion:

The present situation for you as a territory is either uncertain (French territories), certain and as requested but with legal risks (UK-related) or undesirable and legally incorrect (Dutch territories). Maybe it's time to call your fellow territories and together demand the clarity and a clear route how to implement that!My suggestions: after joining, ask your member states to

- change the UPC to explicitly allow extending the UPC agreement to non-EU territories, part of the EPC (and that is a change that doesn't require a diplomatic conference or ratification by all)

- ask your member state to conclude an international agreement between NL, UK, FR and the EU, extending the scope of the Unitary patent regulation to you, in a similar way that many EU regulations are applied to Norway, Iceland and Liechtenstein (the famous "texts with EEA relevance").

Who knows, they well might listen!

Monday, October 19, 2015

the Ukraine-EU Association Agreement up for vote in the Netherlands. ....I think

UPDATE: the Council of State has announced it plans to give its verdict regarding the legal challenge of the referendum on Monday 26 October 4 pm CET. So from that moment we will have certainty on whether the referendum will be held.

In a previous post, I have indicated that a "corrective consultative referendum" may be on its way to the poles in the Netherlands regarding the Association Agreement the EU (but also all its Member States, as well as Euratom) signed with Ukraine.

After parliamentary approval of the agreement in the Netherlands, within 6 weeks, over valid 300,000 requests had to be sent to the Election Council (Kiesraad) to trigger the referendum. Last week, on 14 October, the Election Council announced that threshold was reached exceeded: 472,849 requests were received. Based on a detailed test (name, address and signature match with registered data; person eligible to send the request) of a random sample of just over 4112 requests, ca 90.6% was deemed valid, and thus 427,939 were validated, which means a referendum is to take place.

There is a caveat though, because -as any administrative decision of a government authority- it is open to appeal. In election (and referendum) matters only a single instance appeal is open, directly to the Council of State (Raad van State), and the procedure is designed to be fast: appeals have to be lodged within 6 days (which means Tuesday 20 October at the latest), and the Council of State is to decide the appeal in 6 days of the receipt.

I wouldn't be discussing this, if the Council of State hadn't announced today, an appeal had been filed. An oral hearing date was immediately set for Thursday 22nd, and based on the decision term, that means a final decision will be given on Monday 29th the latest.

According to Geenstijl, this system is in full conformity with the law, and they indicate they checked this with the Election Council. I am not an expert in the interpretation of the law on this point, but think the independent Election Council would have not allowed those forms, if they didn't think they would be within the law. Although we don't know which part of the requests were received using a printed computer-aided signature, according to Geenpeil, only a minority of requests were received through "regular" forms, so an invalidation of those forms will mean that no referendum will be held. But he last word is now with the Council of State.

In a previous post, I have indicated that a "corrective consultative referendum" may be on its way to the poles in the Netherlands regarding the Association Agreement the EU (but also all its Member States, as well as Euratom) signed with Ukraine.

|

| The number of app-based requests received, according to Geenstijl (x= corrected data), via @datagraver |

Effect

The referendum has a consultative character only, but in the case of "NO" vote and a turnout of at least 30%, going against the outcome can not be done quietly: a draft act proposing either entry into force of the rejected act or retraction of that act, has to receive full parliamentary approval before it can enter into force. In the case of a clear decision (>60% NO) it thus seems -to me- unlikely that the law will enter into force, because approving such a law against the majority would equate to political suicide. ... Which means we are stuk with "provisional application" of the EU part of the agreement for an indefinite period, and possibly eventually a new agreement will have to be brokered.

Appeal

|

| Council of State, in The Hague |

I wouldn't be discussing this, if the Council of State hadn't announced today, an appeal had been filed. An oral hearing date was immediately set for Thursday 22nd, and based on the decision term, that means a final decision will be given on Monday 29th the latest.

Are print outs of online requests valid?

I am not sure what the grounds for the decision are, but according to website geenstijl.nl, one of the campaigners for the referendum, the point of contention is the mode in which the requests were received. They had to be sent to the Kiesraad on a designated form, or a "copy" thereof. The Kiesraad itself provided blank forms, as well as the possibility to create a pre-filled form, which only had to be printed and (manually) signed. The geenpeil campaign however, developed a web-based application, that allowed for submission of all required data, as well as the signature (to be produced using the trackpad of a laptop, drawing using a mouse, or using a touchscreen). Requests could not be printed by the applicant, but were stored on Geenpeil's servers, and printed and delivered by Geenpeil. (noone is contending this is a efficient system: the Election Council received the requests and DIGITIZED them before they further processed them)According to Geenstijl, this system is in full conformity with the law, and they indicate they checked this with the Election Council. I am not an expert in the interpretation of the law on this point, but think the independent Election Council would have not allowed those forms, if they didn't think they would be within the law. Although we don't know which part of the requests were received using a printed computer-aided signature, according to Geenpeil, only a minority of requests were received through "regular" forms, so an invalidation of those forms will mean that no referendum will be held. But he last word is now with the Council of State.

Tuesday, October 13, 2015

Immunity of the European Patent Organization: Position of the Dutch Government

In a previous post, I commented on the somewhat precarious situation the Dutch government has found itself in (or manoeuvred itself in, depending on your position) regarding the European Patent Organisation EPO: in a verdict on appeal which thoroughly addressed jurisdiction issues, the The Hague Court of Appeal took jurisdiction in Labour Union SUEPO v EPO, despite the European Patent Convention's Protocol on Privileges and Immunities. It did so in a case regarding non-recognition of the Unions, because labour unions have no recourse to any appeal mechanism, which was a breach of the fundamental rights of its members.

The case was "appealed" in Cassatie to the Hoge Raad (Supreme Court), in a procedure, which is only open to questions on application of (the principles of) law, but not anymore regarding the facts of the case. As I noted, the Dutch government has requested to become a party to those procedures, and was granted that right last month. Now the government has shed some more light on their motives to do so in answer to parliamentary questions of Van Nispen en Ulenbelt. The relevant answer reads (in my translation, with comments in red):

Well, the good thing of this is, that the arguments of the Court of Appeal are now being tested thoroughly at the Hoge Raad, and the State has every right to join the proceedings. But the strength with which the State dismisses a court decision in a case to which it is not a party is also troubling as it touches upon the balance of power between the judicial and the executive branches. It would have been a lot more respectful and appropriate if the State would have followed a different approach and said that "in the interest of development of law" it wants the Supreme Court to weigh the arguments to the maximum extent possible.

Will a decision of the Hoge Raad be the end of the business? In view of the importance of the ECHR case law regarding international organisations, an appeal there seems likely in the case of a loss of SUEPO in the Netherlands

The case was "appealed" in Cassatie to the Hoge Raad (Supreme Court), in a procedure, which is only open to questions on application of (the principles of) law, but not anymore regarding the facts of the case. As I noted, the Dutch government has requested to become a party to those procedures, and was granted that right last month. Now the government has shed some more light on their motives to do so in answer to parliamentary questions of Van Nispen en Ulenbelt. The relevant answer reads (in my translation, with comments in red):

The Dutch State as on 22 May submitted its request to become a party to the proceedings with the Hoge Raad. It did so, because regarding the immunity from jurisdiction and execution attributed to EPO, the verdict of the The Hague Court of Appeal did not take into account sufficiently on one hand the international obligations resulting from the Protocol on Privileges and Immunities of the EPO and on the other hand the special character of EPO, which has a seat not only in the Netherlands, but also in different states. The Dutch state has therefore become party to the proceedings regarding

*The absence of jurisdiction of the Dutch Judge regarding EPO, because of its immunity as an international organisation with a seat in multiple countries [multiple countries argument; I have no idea if the number of seats of an international organization has ever mattered regarding immunity? The point of multiple countries was brought up by EPO of course].

*The scope of the verdict in relation to EPO's immunity from execution

The state has the duty to guarantee that international law is followed in the Netherlands. Violation of international law by the state and its organs leads to international liability of the Netherlands. That means that the State has to guarantee the immunity EPO has. The Netherlands should also ensure that its judges don't take jurisdiction, which they don't have according to international law. This means in the present case that the Dutch judge can not render a decision regarding an organisation over which it has no jurisdiction as a result of immunity. Besides that, the Dutch judge is not competent regarding subjects within the competence of other states. The decision of the court however is directed at the organisation as a whole, including its divisions in other states. For the Netherlands, as a host of EPO and many other international organisations, the international obligation to guarantee immunity is sufficiently important to become a party to the case on the side of this international organisation [after the legal arguments, that is a mostly opportunistic argument].

Well, the good thing of this is, that the arguments of the Court of Appeal are now being tested thoroughly at the Hoge Raad, and the State has every right to join the proceedings. But the strength with which the State dismisses a court decision in a case to which it is not a party is also troubling as it touches upon the balance of power between the judicial and the executive branches. It would have been a lot more respectful and appropriate if the State would have followed a different approach and said that "in the interest of development of law" it wants the Supreme Court to weigh the arguments to the maximum extent possible.

Will a decision of the Hoge Raad be the end of the business? In view of the importance of the ECHR case law regarding international organisations, an appeal there seems likely in the case of a loss of SUEPO in the Netherlands

Monday, October 5, 2015

Conflict of the Conflict of the Laws: jurisdiction involving Choice of Court Agreements

Which court has jurisdiction in international cases is a classic “conflict of law” subject and several instruments exist (bilateral and multilateral), to avoid the unsatisfactory result that the same case is litigated in several venues, and –worse- those venues reach different outcomes.

In Europe, two complimentary instruments exist with regards to "civil and commercial matters": the Brussels regulation applied in the European Union and the Lugano convention in the European Union, Iceland, Norway and Switzerland. A case purely related to the European Union falls outside the scope of the Lugano convention.

Changes: new Brussels Regulation and Hague Convention

2015 saw two important changes to this system: In January, the original Brussels regulation (44/2001) was replaced by a new one (2012/2015). While the old Brussels Regulation was almost to the letter identical to the Lugano Convention, the new Brussels regulation is not. Significantly –and the object of this post– is an exception to the “lis pendens” system, a corner stone of both instruments that indicates that the court seized first has jurisdiction and other courts should stay their proceedings until that first court has given its decision. This provision is to be regarded so strictly, that even if the parties had a Choice of Court Agreement for -say- a German court but proceedings were brought first for an Italian court, that German court would have to wait for the Italian court to determine it had no jurisdiction, before it could take jurisdiction. This sometimes resulted in seizing a non-chosen court being a useful delay tactic (especially when a backlogged court was chosen), informally termed the “Italian Torpedo”. The new Brussels I Regulation addressed this and allowed a court to take jurisdiction, if the court unambiguously was chosen in a valid choice of court agreement; even if parallel proceedings in a different court had been commenced.

The second change is more recent: the entry into force of the 2005 Hague Convention on Choice of Court Agreements. The convention now has two parties: Mexico and the European Union, which means that it applies immediately to 28 states (in addition to Mexico, all EU member states except Denmark). The convention has a much more limited scope than the Brussels regulation or the Lugano convention, as it only applies when a choice of court agreement is concluded. The system is similar to the new Brussels Regulation: the chosen court must hear the case, regardless of any pending actions for other courts. Courts not chosen should declare themselves not competent to hear the case. Also similar to the Brussels system: a decision should be recognised in other Hague convention states, regardless of the merits of the decision.

From 1 October, the membership of those three instruments is as follows:

From 1 October, the membership of those three instruments is as follows:

| Country | EU member | Lugano | Hague Convention |

| Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden and UK | x | x | x |

| Denmark | x | x | - |

| Iceland, Norway, Switzerland | - | x | - |

| Mexico | - | - | x |

Conflict of the Conflict of law measures

So now we have ended up -in the European Union at least at least- with 3 systems to determine international jurisdiction in the presence of a choice of court agreement. Although they all -eventually- favour the agreement, the reasons to reject them varies. Furthermore, the Lugano convention still places the lis pendens regime above the choice of court agreement, so the chosen court will have to wait until the non-chosen court has rejected jurisdiction. It thus matters under which legal instrument the choice of court clause is evaluated.

For the relationship between the Lugano and the Brussels convention is quite clear in this area. If a resident of Iceland, Norway or Liechtenstein is involved, or such a court is chosen, or seized before the chosen court is seized, the Lugano convention will apply, while in cases involving solely the EU, the Brussels convention applies (and yes, there are some areas, where there is ambiguity, but I won't go into that).

The relationship between the Hague Convention and other conventions is treated in article 26 and indicates that the convention should be interpreted as far as possible consistenly with other treaties. The rest of the provisions are complex to read, because they are phrased with many double negations (... where non of the parties (...) is not a member ....). I will try to rephrase them positively, as that is a lot easier to understand. It may however come at the loss of some exactness (possibly when a person should be considered resident in more than one location).

-26(2): Another convention [e.g. Lugano] takes precedence if all parties are residents of

-:'states, which are party to that other convention [e.g. Lugano]; and/or

-:'non Hague convention states

-26(3): If the court seized has conflicting obligations with respect to an older [concluded before the contracting state became a Hague party, e.g. Lugano] treaty with respect to a non-Hague State (e.g. Switzerland).

-26(6)a: The rules of a Regional Economic Integration Organization (REIO, e.g. the EU; applying Brussels Regulation) apply when all parties are residents of

-:'REIO states [e.g. Brussels regulation]; and/or

-:'non Hague convention states'

How does that all work in practice, especially in relation to the Italian torpedo risk? I'll evaluate that using a hypothetical case. The case concerns a dispute regarding a contract with a choice of court agreement favouring "the courts of state A" and the contract parties are party A, resident in State A and party B, resident in State B. When a conflict arises, Party B sues in State C. Subsequently Party A starts a procedure for (the chosen court) of state A. Let's see what happens, when we make A, B and C specific, I get the following applicable instruments:

Case 1 is quite straight forward: if only EU states are involved, the Brussels I regulation applies, and -in its new version- that means no waiting for the Greek court to have decided. Case 2 involves only EU residents, and thus Brussels I applies at well. When residents of only non-EU Hague State Mexico are involved, the Hague Convention applies (example 3).

However (example 5), the French court has the possibility to stay proceedings pending a decision by the Swiss court: under Hague 29(3), the Lugano convention's lis pendens regime is an international treaty obligation which should be respected, as non-Hague state Switzerland is involved. However, this give-way rule only applies when a non-Hague state is involved, so should Switzerland however become a member to the Hague Convention, then the Hague convention should be applied.

In case 7 the EU system applies again, as no non-EU Hague states are involved.

This whole system of examples does not change a lot when other Lugano states become party to the Hague Convention: only in example 5 (Hague 26(3)), Lugano would be inapplicable when Switzerland joins the Hague convention, as it allows only for conventions to gain precedence with regards to treaty obligations in relation to non Hague parties.

Remaining Lugano Relevance

However, the rules under article 26(2) (if only Lugano states are involved + other states that are non Hague states), the Lugano convention applies) are still applicable. That means that the lis pendens regime in the Lugano states can only be resolved through a change in that convention. It puzzels me why no -public- mention of such negotiations is known: the divergence between Lugano an Brussels regulation seems something that politicians have tried to avoid for ages. There must be some hidden problem in the new Brussels regulation as far as the other Lugano states are involved, that hampers the corresponding change in the Lugano convention. Or could it have been that a tactical error has been made in not involving them in the negotiations of the Brussels I regulation recast, and they feel uncomfortable with a "take it or leave it" attitude with regards the corresponding change in the Lugano convention? Who knows!?

For the relationship between the Lugano and the Brussels convention is quite clear in this area. If a resident of Iceland, Norway or Liechtenstein is involved, or such a court is chosen, or seized before the chosen court is seized, the Lugano convention will apply, while in cases involving solely the EU, the Brussels convention applies (and yes, there are some areas, where there is ambiguity, but I won't go into that).

The relationship between the Hague Convention and other conventions is treated in article 26 and indicates that the convention should be interpreted as far as possible consistenly with other treaties. The rest of the provisions are complex to read, because they are phrased with many double negations (... where non of the parties (...) is not a member ....). I will try to rephrase them positively, as that is a lot easier to understand. It may however come at the loss of some exactness (possibly when a person should be considered resident in more than one location).

-26(2): Another convention [e.g. Lugano] takes precedence if all parties are residents of

-:'states, which are party to that other convention [e.g. Lugano]; and/or

-:'non Hague convention states

-26(3): If the court seized has conflicting obligations with respect to an older [concluded before the contracting state became a Hague party, e.g. Lugano] treaty with respect to a non-Hague State (e.g. Switzerland).

-26(6)a: The rules of a Regional Economic Integration Organization (REIO, e.g. the EU; applying Brussels Regulation) apply when all parties are residents of

-:'REIO states [e.g. Brussels regulation]; and/or

-:'non Hague convention states'

How does that all work in practice, especially in relation to the Italian torpedo risk? I'll evaluate that using a hypothetical case. The case concerns a dispute regarding a contract with a choice of court agreement favouring "the courts of state A" and the contract parties are party A, resident in State A and party B, resident in State B. When a conflict arises, Party B sues in State C. Subsequently Party A starts a procedure for (the chosen court) of state A. Let's see what happens, when we make A, B and C specific, I get the following applicable instruments:

| A | B | C | Applicable instrument in state A | lis pendens? | |

| (party A, Chosen courts) | (party B) | court first seized | [applicable Hague "advantage" provision] | ||

| 1 | France | Belgium | Greece | Brussels I [Hague 26(6)] | no |

| 2 | France | Belgium | United States | Brussels I [Hague 26(6)] | no |

| 3 | France | Mexico | Greece | Hague | no |

| 4 | France | Belgium | Switzerland | Lugano [Hague 26(2)] | yes |

| 5 | France | Mexico | Switzerland | Lugano [Hague 26(3)] |

yes |

| 6 | Switzerland | Mexico | France | Lugano | yes |

| 7 | France | United States | Belgium | Brussels I [Hague 26(6)] | no |

| 8 | United States | France | France | - | no |

Case 1 is quite straight forward: if only EU states are involved, the Brussels I regulation applies, and -in its new version- that means no waiting for the Greek court to have decided. Case 2 involves only EU residents, and thus Brussels I applies at well. When residents of only non-EU Hague State Mexico are involved, the Hague Convention applies (example 3).

However (example 5), the French court has the possibility to stay proceedings pending a decision by the Swiss court: under Hague 29(3), the Lugano convention's lis pendens regime is an international treaty obligation which should be respected, as non-Hague state Switzerland is involved. However, this give-way rule only applies when a non-Hague state is involved, so should Switzerland however become a member to the Hague Convention, then the Hague convention should be applied.

In case 7 the EU system applies again, as no non-EU Hague states are involved.

This whole system of examples does not change a lot when other Lugano states become party to the Hague Convention: only in example 5 (Hague 26(3)), Lugano would be inapplicable when Switzerland joins the Hague convention, as it allows only for conventions to gain precedence with regards to treaty obligations in relation to non Hague parties.

Remaining Lugano Relevance

However, the rules under article 26(2) (if only Lugano states are involved + other states that are non Hague states), the Lugano convention applies) are still applicable. That means that the lis pendens regime in the Lugano states can only be resolved through a change in that convention. It puzzels me why no -public- mention of such negotiations is known: the divergence between Lugano an Brussels regulation seems something that politicians have tried to avoid for ages. There must be some hidden problem in the new Brussels regulation as far as the other Lugano states are involved, that hampers the corresponding change in the Lugano convention. Or could it have been that a tactical error has been made in not involving them in the negotiations of the Brussels I regulation recast, and they feel uncomfortable with a "take it or leave it" attitude with regards the corresponding change in the Lugano convention? Who knows!?

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)